It’s been three months since I posted my last blog entry, as I was preparing to record a number of works by Morton Feldman for multiple pianos from the late 1950s to late 1960s, including some with instrumental ensemble. The recording session took place in late June and I’ve recently been working with Simon Reynell from ‘another timbre’ on the edits for the double CD.[1] So I now feel ready to offer a few reflections on the music and our performances.

Firstly it was one of the most enjoyable weekends of music making I’ve had for a long time. The music reignited my love for Feldman’s work, which to be honest goes in waves – I think if there’s ever one composer whose music one can over-indulge in it’s Feldman. I tend to have periods when I am absorbed in the work totally and without reservation and other times (often up to a few years) when I don’t want to hear a note! However, the works we recorded, three of which I didn’t know – Two Pieces for Three Pianos (1966), False Relationships and the Extended Ending (1968) and Between Categories (1969) – blew me away. I think they are amongst Feldman’s absolute greatest works.

Working with the musicians involved in the project was a joy. How often does one get to work with three great pianists on the same day? Mark Knoop, Catherine Laws and John Tilbury are pianists whom I hold in enormous respect and their commitment to the music, to sound and touch, to nuance and to each moment made for such an enthralling weekend. We all probably approach Feldman’s piano music in subtly different ways and yet with a common appreciation for the values and sensibility required to perform it. It’s really fascinating to hear us play Piece for Four Pianos (1957), in which we all move through the same one-page score at our own pace. The sound of four quite different touches is clearly perceptible – we made no attempt to aim for uniformity – but the character of the music feels entirely unified.[2] There is a sense of the four of us enjoying listening to each other and responding, though at the same time there are many unpredictable moments that feel quite Cage-ian. (At the end of the recording session we recorded a 40-minute version of Cage’s Winter Music, which was also exhilarating, but that’s for another blog maybe!)

And then to perform with a wonderful array of musicians, some of whom I know very well, and others less so, was also a great privilege. Naomi Atherton (horn), Mira Benjamin (violin), Taneli Clarke (percussion), Rodrigo Constanzo (percussion), Linda Jankowska (violin), Anton Lukoszevieze (cello), Barrie Webb (trombone) and Seth Woods (cello) – all wonderful, insightful and committed performers. The two large ensemble pieces, False Relationships and the Extended Ending and Between Categories, which were unknown I think to most of us, were fascinating to play. There was a real sense of being in the heart of the experiment whilst playing these pieces, combining attentive playing to our instruments with curiosity and surprise at the sounds going on around us.

I want to reflect a little on the four pieces which involve what might be called ‘interdependency’ – Piece for Four Pianos, Two Pieces for Three Pianos, False Relationships… and Between Categories. These works are in some ways difficult to prepare; their form and relationships are worked out very much in the performance moment. Each of them requires performers to move through the music independently in some way: Piece for Four Pianos as described above; the first movement of Two Pieces… requiring no coordination between the three pianists; and the other two featuring two separate ensembles, with their own material and notations, moving through the music at their own pace, at times precisely with rhythmic details and metronome marks, and other times with simple noteheads without duration. The confusing quality of these two is that performers all read from the same score, which often gives the appearance of alignment between the two ensembles but in fact they are likely to be fairly significantly adrift at any point in time (or rather, on the page).

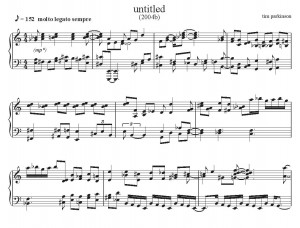

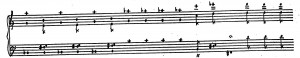

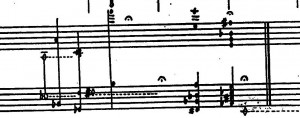

Piece for Four Pianos is one of my all-time favourite works by Feldman, a view I think shared by many people. The simple concept of the same single page of music, given to all four pianists, with durations of events free, results in some of the most entrancing music, and is I think quite unique amongst the output (though the slightly earlier work Two Pianos works according to the same principle). What I hadn’t perhaps felt so keenly in the past was that as well the gorgeous sonorities of the opening section (example 1) and later passages which involve a number of repeated chords (so that, for example, if there is one chord notated four times in succession, one is likely to hear that chord 16 times, creating a wash of harmonic stability) there are also a number of stranger passages, involving more silence and a feeling of harmonic instability. Most odd, perhaps, is the final line (example 2), which follows an extended section of harmonic stability, due to a repeated figuration, and features the most dense and dissonant chords in the whole piece. Not only do these feel strongly contrasting to the rest of the piece, suddenly shifting into a new galaxy having become accustomed to the atmosphere of the planet on which we seem to have landed, but these are also the most difficult and exposed chords to play. It feels rather cruel of Feldman to have ended so, and certainly these few chords had me breaking into a sweat – after all, if I misplaced these then the whole performance might have to be scrubbed! But of course they make for an enigmatic and curious ending, as if Feldman himself was also very aware of the dangers of over-indulging in his soundworld.

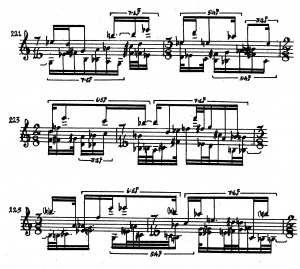

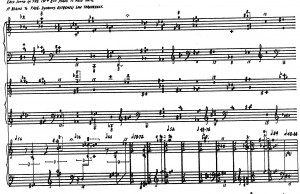

The sparse sound and density which marks Piece for Four Pianos is in total contrast to the first of the Two Pieces for Three Pianos, which features very dense piano chords, a number of which are simply impossible to stretch (even for Feldman’s apparently large hand-span; see the third and fourth events of the second piano part in example 3). The challenges for the pianist here, aside from trying to project the best quality and quietest sounds from these awkward combinations of notes, are in allowing the music to sound free whilst at the same time measuring it against the sounds of the other pianos. Whilst the first two pianists can probably keep tabs on each other’s progress (though in the event I chose not to, opting instead for listening rather than ‘watching’) the third piano takes off at quite a pace, with a first bar which lasts around nine seconds, a second bar which lasts around four seconds (despite measuring about a fifth of the length of the first bar on the actual page), and so forth. Listening back to the recording, the third pianist’s first line was completed by the time the first two pianists had played about two-thirds of the line. Whilst it might be possible to follow this in performance I certainly chose not to and instead focussed upon the instruction that each sound ‘is held until it begins to fade’. This instruction is the crucial one – it sets the pace for each event but also for the whole piece. On the whole the pacing averages out between these two parts, and pianist 1 and 2 ended at roughly similar times in each take. The third pianist, whose part is measured precisely throughout, ended before the first two pianists in each take. Playing this music – and the same is true for all the pieces discussed in this blog – I felt totally alive in each and every moment, in a very similar manner to my experiences of playing Cage’s post-1951 ensemble music. The pleasure of playing this sublime music whilst at the same time being fascinated and delighted by the sounds being made around me is wholly exhilarating – music very much for playing, as well as for listening.

False Relationships and the Extended Ending and Between Categories were no less a joy to play.[3] Many of the comments above apply to these pieces, but the notation for each ensemble within each piece, shifts during the piece, so that one time one ensemble might be playing strictly metred music whilst the other plays noteheads without duration, and vice versa. Again, following the other ensemble in both pieces is very difficult – I don’t think any of the performers attempted it. Quite often the ensembles are one or two (possibly even more) pages apart, yet we follow the same score. A combination of counting and listening is what determines the pacing and coordination of both pieces. This was made a little more difficult in Between Categories, however, due to both ensemble consisting of the same instruments (violin, cello, chimes, piano), so the occasional sound of the chimes from the other ensemble occasionally threw me into panic thinking it emanated from my ensemble.

As my previous blog testifies, there were a number of questions I had about how we would approach coordination that I’d thought would be clarified through rehearsal. As it turned out, no clarification was required – we played and it worked. How exactly that worked I’m not entirely sure, but is to Feldman’s great skill and his understanding of the natural pacing of each ensemble, despite the apparent freedoms that the notation offers, that credit must be due. In the rehearsals themselves and still now I marvel at how this came about. In my last blog I cite Brett Boutwell’s excellent writing about these pieces[4]; he writes about Feldman’s layout of the score for False Relationships…, from his sketches, which demonstrate a central coordinating point on page 8 (which would not otherwise be obviously discernible without access to the sketches). In performance there was no intention on any of our parts to arrive at this point, however it was heartening to discover that in each take (other than a rather more exploratory first take) we did indeed arrive at page 8 at around the same time – no exact coordination, but, after quite a long time of being one or two pages apart, the coming together at page 8 feels entirely natural, unforced. However, in contrast to Boutwell’s suggestion that the first ensemble to end on the score is actually the last to end in time, in each of our takes this first ensemble did also end first. There was no sense that anyone was moving ‘too fast’ or ‘too slow’ and so we made no attempt to change this natural order of things.

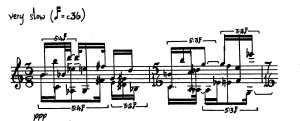

Applying Boutwell’s discoveries in False Relationships… to Between Categories I was delighted to discover a comparable point, here later in the piece than the mid-point of False Relationships…. The beginning of the penultimate page (page 8) features for the first time since page 2 a double bar line, which is aligned across both ensembles. After having been apart for one or two pages for most of the piece, in each of our takes the ensembles did in fact arrive at this point approximately together (if the pause that ends page 7 for the first ensemble had been a little longer in one take then page 8 would have begun as a simultaneity). Now’s not the place for an analysis of the pitch content at these apparent coordinating points but it would be fascinating to understand more what the significance of these points was to Feldman. Between Categories is an exquisite work; the shared material between the ensembles recalls the more simple processes of Piece for Four Pianos but now within a more complex setting, and the relationship between the ensembles is rich and satisfying.![]()

These extraordinary works deserve to be played and known more. They reveal a composer who is not only rightly revered for his attention to sound and sonority but who was also, despite what I wrote in the opening paragraph of my previous blog, a master of notation, form and design.

[1] To be launched in November at hcmf 2015 alongside a concert featuring the works for multiple pianos alone http://www.hcmf.co.uk/event/show/426

[2] In my previous blog I raised the question of black noteheads vs white noteheads. In discussion with the other pianists we all had slightly different views on how to approach these. In many ways this was an issue of language and imagery, but also differences of touch and attack. We agreed not to resolve this and conform to one idea but we did all agree that for each of us the difference of notehead provoked a difference in touch and sound in some way. That was sufficient!

[3] The pieces are closely related, procedurally but also in content – there is an arpeggiated piano chord which occurs in both pieces, and is a recurring feature of Between Categories.

[4] Brett Boutwell ‘”The Breathing of Sound Itself”: Notation and Temporality in Feldman’s Music to 1970’ (Contemporary Music Review, 32/6 (2013), 531-570); and also ‘Coordinating Morton Feldman’s False Relationships’ Mitteilungen der Paul Sacher Stiftung No. 23 (April 2010): 39–42