The piano music of Tim Parkinson exemplifies perfectly for me the classic duality which I find in much experimental music (from Cage to Crane, White to Wolff) of being both anti-pianistic and gloriously pro-piano. This was brought home to me in a performance I gave last week of Tim’s untitled 2004b (the first performance of this work, ten years after it was composed) alongside James Clarke’s Island (1999), at the London Contemporary Music Festival.[1]

I love the music of both composers very very much, and there is much they have in common – in particular a concern for musical material and its use which is primarily abstract, demonstrated by the choice of both composers (Clarke in more recent years) to give their pieces titles which are merely labels, such as the date of composition or catalogue number of the work. But there is no doubt in my mind that James’s music is situated within a context of Western notated music, whereby the harmonic and structural language is entirely his own but the gestural and physical language is borne from the ways in which traditional music notation makes the performer move and, in the case of Island, how the pianist moves. James’s extraordinary harmonic sensibility, his understanding of form, texture and movement, combine so that it’s almost impossible not to be swept up by the organic drive of the music. Playing it I found that the music carried me through it, that my job was to go with what’s already there and to bring out those elements, such as the various states of volatility and uneasy calm, the dark brooding opening section, and the waves of rapid notes which elaborate the harmonic scheme.

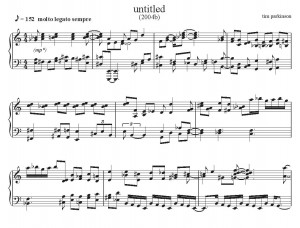

The abstract concoctions of Tim’s untitled 2004b, however, require the opposite approach to performance. The harmonic language, whilst not untypical of his music, could not be said to be a mark of individuality in the same way as it is in James’s music. The material of Tim’s music generally draws much more upon historical models and could broadly be said to be a mix of chromaticism and tonality, or taken from tonal models, though it certainly doesn’t function tonally. Although it feels familiar – and indeed looks more familiar than some of the intricacies of James Clarke’s notation – the material is drained of all rhetorical context that we may normally associate with it (even though we cannot place the material exactly it feels familiar but is somehow an empty shell of something once infused with expressive life). All that is left are notes – pitches, durations and patterns. The score is marked sempre mp (although in my performance last week the composer and I agreed to make it sempre mf for acoustical reasons). The task is to accord no intentional priority to any material at any time, neither to right nor left hands, nor to higher or lower material, nor to material which might be considered melodic or harmonic, leading or accompanying. At all times the material should feel, at least to me as performer, equally ‘plain’. Flat. Anonymous.

This is the biggest challenge and for me the most exhilarating one. Because once I feel I have achieved the required equilibrium the material is then in a position to be expressive in and of itself. It needs no context. Every moment is a winner. This is what I mean by it being both anti-pianistic and pro-piano. I have to consciously work to negate the pianistic impulses that are suggested by the material – namely, at times to favour one hand over the other, at other times to shape a group of notes according to informed and intuitive impulses, at other times to let the music ‘groove’ – almost to ‘deny myself’. Paradoxically this requires a conscious raising of dynamic or intensity to some material which would perhaps intuitively be overshadowed by other material. Once this has been worked at and achieved then my attention comes back to touch and presence, and a re-engagement with the piano. Here is where I think Tim’s music differs from, say, that of Chris Newman, where arguably a more crude approach to touch and projection might be called for. In untitled 2004b my focus all the time is upon clarity, evenness, transparency. I don’t want anything to get in the way of the music. This sounds like a non-interpretative approach but of course such an approach is itself highly aware and intentional.

I would apply – and have applied – a similar aesthetic and interpretative attitude to other music by Tim. untitled 2004b differs from other works by him that I have played through the sheer density of material. The more pared down music of, say, piano piece 2006,[2] has its own challenges – less clutter means more of the inconsistencies in my touch can be heard and the difficulties of playing a simple scale slowly, evenly, at a consistent dynamic are revealed for all to hear! untitled 2004b, with its abundant material, multi-layered across the hands, is a much busier work, too much to take in, and feels to me to relate most of all to Cage, strangely most of all to the Music of Changes. Once fingering has been worked out to enable a smooth movement through the material all that is left to do is to quite literally work my way through it. In contrast to how we are generally taught to play music there is no need to find or make connections, nor to consider shape and flow. And as I wind my way through the piece I find that each and every moment has real quality. It’s a great trip and, although it’s technically tricky in places, my overall state playing it is one of joy.

[1] www.lcmf.co.uk The concert consisted of a first part which included my playing with Gavin Bryars, Chris Hobbs and John Tilbury in two of Chris Hobbs’ pieces from the 1970s, and then a second part in which I alternated two solo performances with vocal improvisations from the wonderful Maggie Nichols

[2]I recorded piano piece 2006 and piano piece 2007 for Edition Wandelweiser